Altars & Artists: Jaidyn Luke Attard

Interview 11: on becoming 'The Street Poet', revitalising punk zine culture, and witnessing beauty and hardship on the streets of Melbourne

Welcome to Altars & Artists, a monthly interview series divining the poetry of artists' spaces. Inspired by Gaston Bachelard’s book "The Poetics of Space" and Virginia Woolf’s extended essay "A Room of One’s Own", Altars & Artists delves into the creative spaces of contemporary artists to reveal the intimate worlds they operate within.

New to this series? Be sure to check out the intro post below:

Please welcome our May Altars & Artists guest: Jaidyn Luke Attard

Jaidyn Luke Attard (he/him) is an author, street poet and indie publisher shaking up the literature scene on Wurundjeri land. He lives for literary mischief and poetic disruption. His typewritten poetry can be found across Victoria, left behind for people to find as part of the street poetry movement materialising in Melbourne, blurring the lines between street art and contemporary poetry. With punk-rock spirit and a D-I-Y ethos, he founded Back Shed Press in 2021—a grassroots distro championing raw, rebellious voices in Melbourne, offering emerging writers the opportunity to be published in zines, anthologies and chapbooks. He has also worked as a bookseller for the past eight years and considers himself a ravenous reader.

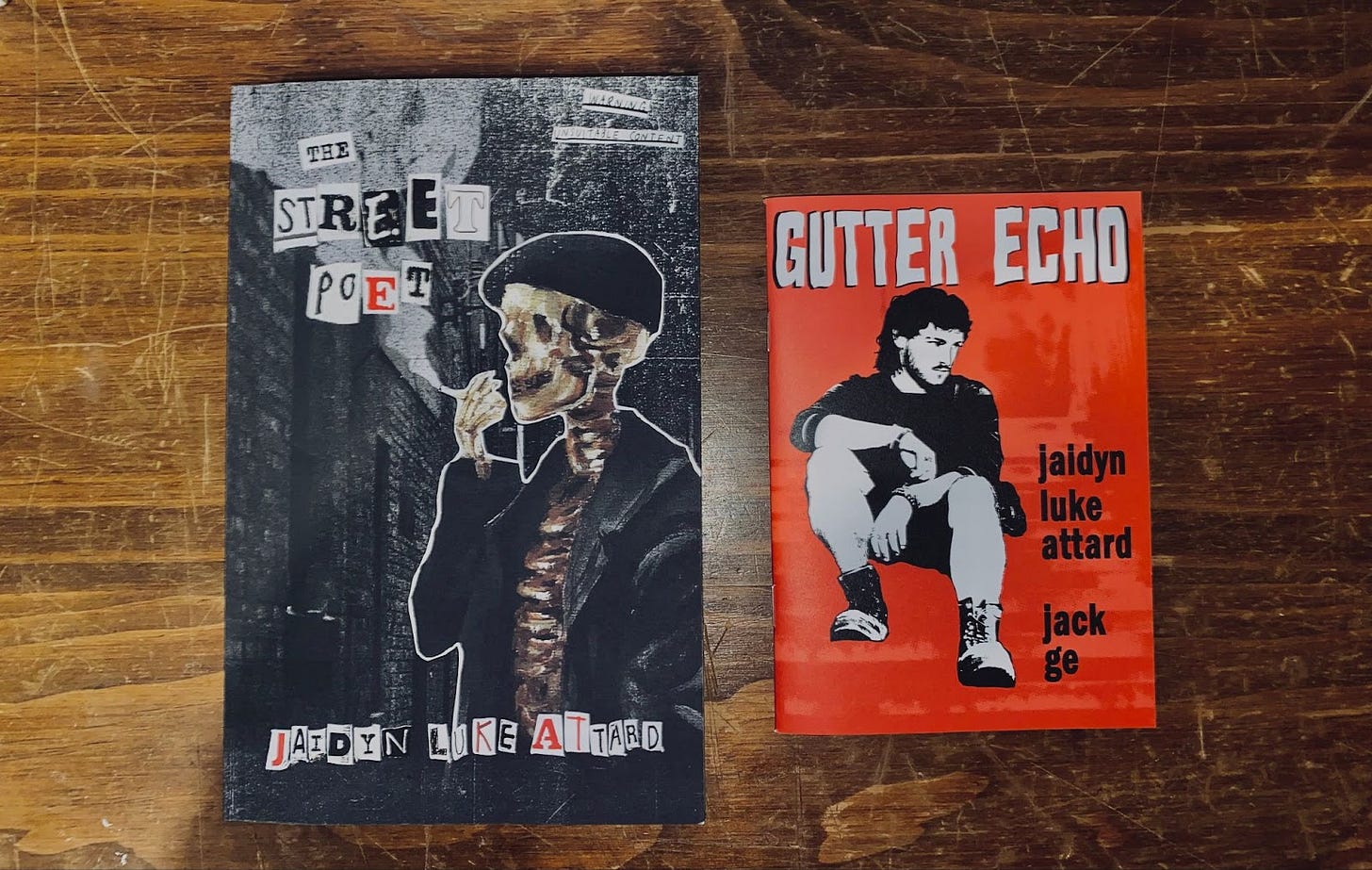

His autofiction verse novel, The Street Poet (2023), captures a young drifter’s search for meaning in the chaos of the urban world, via his encounters with strangers in the underbelly of Melbourne. An expanded edition of The Street Poet drops later this year.

SUBSTACK | INSTA | YOUTUBE | BACKSHED PRESS

Questions & Curiosities

Welcome to Ruminations, Jaidyn! Would you please tell us a little about yourself and your creative work?

JLA: Hello! Thanks for having me on, I’m delighted to be here! For me, the written word is my medium, and the blank page is my canvas. I’ve called myself a writer since I was little, which became self-fulfilling, I suppose, because it’s what I am today. I am an author and street poet writing on Wurundjeri land in Melbourne.

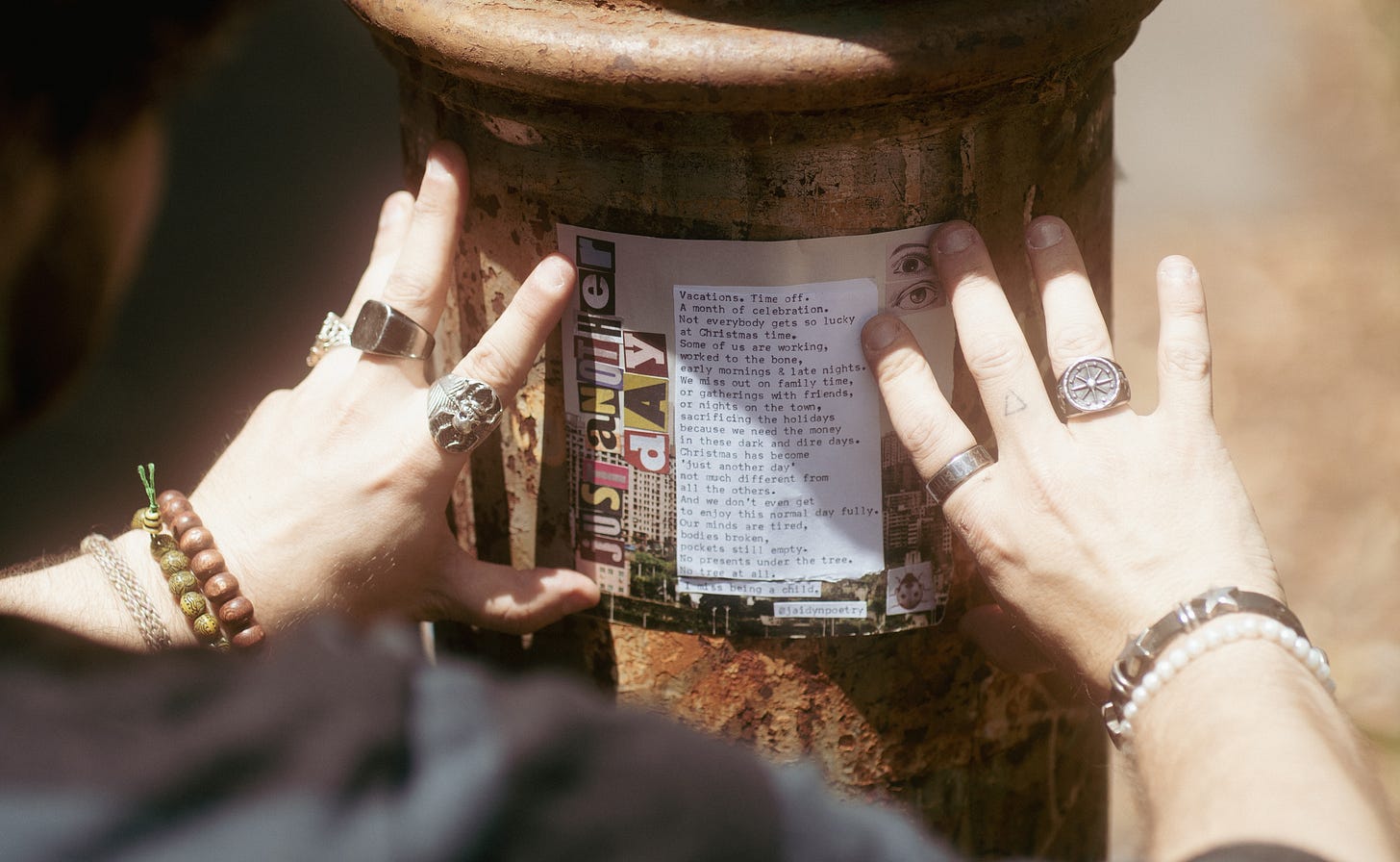

For the last few years, my main focus has been experimenting with observational poetry about my own real-world encounters in urban conditions. I also do this thing I call ‘street poetry’ where I leave poems around in public places to try and spread some joy to strangers or provoke them into some sort of inner reflection. I’ve also started up my own DIY-driven small press to publish zines and chapbooks by other writers.

But my first love is the novel. I enjoy nothing more than the process of crafting fictional stories, which I am planning to do a lot of in the future.

Your debut poetry collection, The Street Poet (2023), bears witness to a gritty 21st-century Melbourne, “…a city flashing between hot and cold, welcoming and discordant”. Although it follows the journey of young, paranoid writer Johnny Lock, the auto-fictitious nature of the poems lends the collection an unmistakable rawness and palpability. How has writing (and becoming) The Street Poet shaped these last few years for you?

JLA: Writing that book has been the defining event of my twenties, which surprised me because that wasn’t my plan at all! I’ve learned more about life and people by writing street poetry than I could have at school. None of my tertiary education in writing and publishing could actually prepare me for the reality of being an author—my own journey has turned out to be an unconventional one. My expectations were subverted in every possible way.

For the longest time, I thought I was going to be a fantasy writer. I spent all of high school and university on sweeping tales of magic and war. I had never even tried to write anything else, it wasn’t on my radar. I was also trying to land an editorial position in publishing, convinced it was the only pathway that offered a chance at stability. I didn’t realise how rare stability actually is in that world. Then, in my twenties, life in all its twists and turns got complicated, and COVID turned our lives upside-down. My mental health took a spin for the worse, and every day felt like struggling to survive. So I turned to poetry for catharsis, and then to paste-up poetry art for community interaction. I just leaned right into this punkish, expressive outlet as a coping strategy. I think it worked.

The adrenaline that came with pasting up my poetry and meeting strangers in the urban wild fulfilled me in new ways. I wasn’t sure where all of this was leading me at first, but then The Street Poet happened, and now I know: okay, so I’m an author, and that means I need to keep writing books. I’m enjoying being an author and sharing my poetry too much to even think about doing anything else now.

Making The Street Poet meant adopting both ‘author-mode’ and ‘publisher-mode’ at once, which is just my default mode now. It’s very hands-on. Being an author takes up most of my time when I’m not at my day job, which isn’t very punk of me to admit. I even had to go into bookshops myself to ask if they would stock it, and for every acceptance there were at least two rejections. I was totally out of my depth, but ‘fake it to you make it’ has some truth in it. I figured it out along the way, and it feels like I’ve lived a lifetime in just a few short years.

I remember reading your book and being struck by its deeply honest tone and your devotion to observation. Your poetry doesn’t shy away from chaos or discomfort, but neither does it embellish or overly romanticise. I wondered if you might be able to speak to the role of noticing in your street poetry, and also in the way you interact with your city and its people.

JLA: Yes, noticing! Well, it began as a way to manage my own anxiety, grounding myself, being in the present and so on. I think one of the reasons noticing, or people-watching, appealed to me was that it felt like a kind of meditation. Observing helps me step outside my own head. It requires tuning out of my troubles and focusing on what unfolds around me. It’s the whole flâneur idea. I tend to pick up on the seemingly small overlooked details, and those peculiar irregularities are so fascinating to me. I write these encounters as poetry to make sense of them.

I came to recognise patterns in the city of Melbourne by doing this. Beauty and hardship side by side on the streets, and a whole lot of grey in between. I noticed people behaved in different ways, and I would ruminate on why. In particular, the harsh reality of those living with homelessness and addiction became apparent to me, and by talking to some of the people experiencing this, I came to deepen my understanding of class and the nuances of society and humanity. Now I see these recurring characters, some of whom I interact with regularly, as one might with friends.

All of this has taught me that compassion is crucial in this modern world of hustle and capitalism. I challenged a lot of my preconceived ideas by engaging with urban life differently. Federico Garcia Lorca said, “I will always be on the side of those who have nothing and who are not even allowed to enjoy the nothing they have in peace”, and I think this informs a lot of my interactions with the city and its people. I hope some of my poetry can help others see things from new angles. Maybe people will be able to view their own urban landscapes a little differently, too.

Would you say that Melbourne city, even, is something like an altar to you?

JLA: Absolutely. The urban places I frequent are the ones that most inspire my creativity. It started by accident, because I was always passing through these spaces, so proximity has something to do with it. But I can’t really seem to stop myself from returning to the city whenever I get the chance. I even like to sit on the side of the street and write in my journal as the city moves on around me. I often find somewhere to sit and read a book after work, in that last hour of daylight before the sun goes down. I find my own street-side reading nook, somewhere to lean, to compose my thoughts or stop to observe the world I live in. The State Library of Victoria is probably my Altar of the Street. I live sitting outside the library. I often come home with stories to tell.

Let’s leave the city behind for a moment and turn to your own creative spaces. Will you walk us through them, Jaidyn?

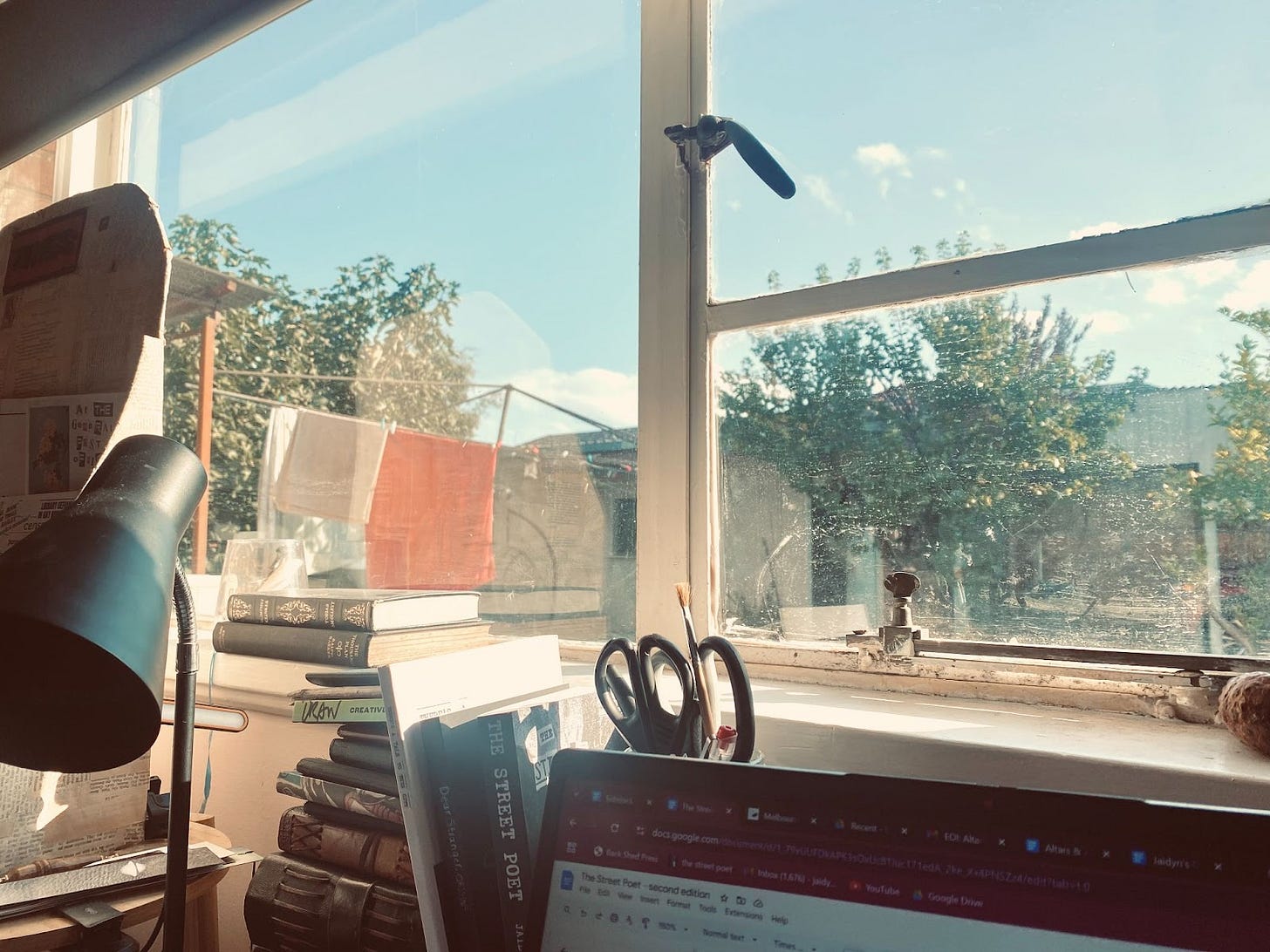

JLA: My main altar is what I call my office or studio. It’s just one of the spare bedrooms in my sharehouse, which I’ve turned into something of a library and desk space. I love to surround myself with books—old books, new books, books I’ve read, books I’m going to read, books I’ll probably never get the chance to read. I work in a bookshop as a day job for this very reason. Being around books just inspires me to keep creating, keep telling stories, and it reminds me to never stop engaging with other storytellers.

It’s important to me to have this designated space that is for ‘writing-related activities’ so that, when I’m in there, I do not get distracted. I try to keep my desk semi-organised so I don’t slip into inertia and stress, but it does get cluttered with books, papers and coffee mugs. This is where I do all of my laptop work. Writing, editing, graphic design, admin. I keep important notes and dates tacked up above, and the window is usually open if I’m working in the office during the day, so the sun can shine through.

My desk is covered in stickers, perfectly representing my chaotic mind.

The wall behind my desk is a large wall collage of magazine cutouts, typewritten poetry, illustrations, artworks and quotes that inspire me. Whenever I have to move into a new place, the collage wall is the last thing to come down. It’s one of those things that makes a space my own.

In my office, I also have a shelving set-up for all of my own books, as an author, and all of the zines I print and distribute for a small writer’s collective here in Melbourne, as part of my Back Shed Press responsibilities. I keep the zines inside so they don’t get chewed on by mice or get damp out in the shed.

My office window looks out into my backyard. The lopsided clothesline reminds me I have clothes to take down and fold. The fig tree, which we made jam from this year.

And the shed—of course, the shed! Back Shed Press is named after the shed, because these are good working spaces for groups of people coming together to collaborate. I like designing my creative spaces so that others can join in and be involved, because the process of creation can be very solitary and lonely. I’m hoping some of my fellow writer-friends can get together in the shed sometime and parallel-create their own zines or projects side by side. It’s a great environment for creating.

I’d love a glimpse into your creative process. I’m curious to know if different stages of creation are tied to different places for you.

JLA: My creative process changes depending on what it is I’m working on. When I’m cutting out magazines and words from old dictionaries and turning them into collage pieces or street poems, I’ll usually do that in the Back Shed—night or day, it doesn’t matter. The whole world disappears for a few hours when I have my precision blade, my typewriter, and those old magazines. It gets pretty messy, with paper scraps all over the place and glue stuck to my fingers, but that’s why I’m out in the shed, right? It’s a good place to contain the chaos.

When it comes to writing about my street observations, these—as you would guess—start on the street. My eyes are the camera, my journal or notes app becomes the recorder. I rarely write a full poem on the spot. It usually looks like rough notes, transcribed dialogue, character descriptions, etc. Maybe I’ll come up with a few lines or a stanza or two, but the poem really takes shape when I’m in my office, at my desk, turning those notes into a poem or else typing something up spontaneously on my typewriter. So the poems start on the street, lead to the office, and then sometimes end up back on the street. It’s all a weird cycle, in a way. I love it.

As for writing a novel … I don’t think I can do that if I’m not in my office. I don’t really like to take my laptop out to write in public places, because the last time I did that, someone stole it. I still haven’t recovered from that. So I only work on my long-form writing at my desk, in the typical brooding writer fashion. Unless it’s winter—I have done a lot of writing from my own bed in winter because it’s often the only place to keep warm at night. I mostly prefer to write late at night, usually between the hours of 10 pm and 2 am. I know, I’m insane. But I just prefer the night for creativity and the day for work, admin, life. Once I start writing, I need to be physically exhausted to pull away from the page. When I do write during the day, I often end up writing from morning until dark like it’s a full-time job.

Are there any writers or artists who inspire you or who have informed your approach to craft?

JLA: Too many. In terms of the themes I tend to write about, authors like Trent Dalton, Irvine Welsh and William S Burroughs have been enormous inspirations for me—especially the more experimental cut-up method Burroughs and Kathy Acker were known for. I like doing that with my poetry. Hunter S Thompson, too, with his gonzo stuff. You could call street poetry a bit of an offshoot from gonzo journalism, if it helps explain what I’m trying to do with it.

One artist I admire is Patti Smith. She writes, she sings, she paints, she takes photos. She is an artist in every sense of the word. I aspire to be able to do all of those things too, to not limit myself to one box of creativity. That’s why I do spoken word stuff, stick up my street poetry, and film really out-there videos for YouTube. I think Patti has helped me reframe the kind of artist I want to be, and she gives me a lot of hope that all of the struggle will be worth it. And she’s vocal. That’s important. I think my work is pretty vocal.

And I can’t leave out

. He’s an author, street writer, film grip, seasoned traveller—and my best friend. I’ve co-written with him before, and we often still write together, usually over FaceTime because he no longer lives in Australia. We even have another book coming out at some point. Jay was the turning point for me, especially with the street poetry. He taught me that if I wanted to be a writer, I simply had to be one. I had to stop making excuses, stop waiting for the right time. I don’t know if I would have published The Street Poet if I hadn’t met him. He’s an incredible writer.What is one thing you believe every artist’s space should have?

JLA: An artist, of course! What’s the point in having all of these tools if no one’s there to use them? I mean, spaces can look different for everyone. A sculptor’s space is going to look very different from a writer’s space, a film-maker probably has a gazillion cameras and lighting rigs and green-screen walls and other wacky things that my spaces don’t have. And … I mean … street poets don’t even need a specific space to start creating. They just need themselves, something to write with, and their observational skills. Their spaces can change from moment to moment, because they’re writing about their environments.

Maybe everyone needs something to write in and a pen. Every artist's space should have those. Every kind of artist can find use in a notebook and a pen, I think. Maybe that means writers are superior. Haha. Kidding.

Despite its cheekily blank ‘WHO WE ARE’ page, I know you to be the founder of Back Shed Press, an independent publisher revitalising punk zine culture and blending contemporary writing with the punk ideologies and aesthetics. What drew you to zines personally, and why do you think they’re important now?

JLA: Ah, zines! I love making zines. I don’t think I’d ever even heard of them until a few years ago. A lot of people aren’t familiar with zines. They aren’t exactly mainstream literature.

Well, zines are independently made publications, sort of like small-scale magazines, made for love and easy distribution. They’re usually made with a photocopier and assembled with a stapler, DIY-style, keeping production costs low and making them accessible for just about anyone to be involved with. Anyone can make a zine, really, because zines can be about anything. They were popularised out of old sci-fi magazines, comics, the punk rock scene in the 70s and the riot grrrl movement of the 90s.1

The reason I love zines so much is that they aren’t gatekept like a lot of literature. There’s no barrier stopping people from entering the scene. There’s no publisher at the end of the line sending off rejection letters. They’re a great entry point for writers trying to find a creative rhythm and work up the confidence to work on bigger projects. That’s what I’m trying to do with Back Shed Press. Publishing is hard, but writing is supposed to be enjoyable, right? I’m trying to show other writers that they can actually get their writing out there without needing to be a published author. Which is punk as hell.

“The reason I love zines so much is that they aren’t gatekept like a lot of literature. There’s no barrier stopping people from entering the scene. There’s no publisher at the end of the line sending off rejection letters.”

Punk is a working-class genre, which is where I sit on the class spectrum. Imbalances between the working class and the elite upper class are widening. It’s hard to get ahead when you’re just trying to survive. Most of us feel it. That’s why zines are increasingly becoming the perfect outlet for punks and poets alike, and it’s why I’m encouraging more writers to try their hand at them. Social media is so full of advertisements and influencers, and it’s harder now than ever for artists to be noticed. It sort of feels like creating our own media in a grassroots kinda way.

My latest release was a zine, actually. It’s a 50-page zine called Gutter Echo, which is another collection of street poetry and photography about Melbourne. I’m actually really proud of it. It’s a good way to continue sharing my writing in between novels.

A note for free subscribers

To continue reading this interview and unlock the creative prompt, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Doing so gives me the time to find and interview other inspiring guests for Altars & Artists. Your contribution also keeps Ruminations running & this lil writer at her desk! <3

You know I had to ask—can we have a peek at The Back Shed?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ruminations to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.