Altars & Artists: Mabel Gibson

Interview 09: on writing and publishing micro memoir, collectables and curios, and embracing being a crybaby

Welcome to Altars & Artists, a monthly interview series divining the poetry of artists' spaces. Inspired by Gaston Bachelard’s book "The Poetics of Space" and Virginia Woolf’s extended essay "A Room of One’s Own", Altars & Artists delves into the creative spaces of contemporary artists to reveal the intimate worlds they operate within. ❧

New to this series? Be sure to check out the intro post below:

Please welcome our March Altars & Artists guest: Mabel Gibson

Mabel Gibson is a twenty-five-year-old Yamatji writer. She grew up in Boorloo (Perth), Kinjarling (Albany), and Jambinu(Geraldton), three vastly different locations with landscapes and climates that all play an important role in her story. Her work has been published in maar bidi: Next Generation Black Writing (Magabala Books), all four Night Parrot Press anthologies, and Portside Review. She has sat on panels at various festivals including Perth Writers Weekend, Ubud Writers Festival, and Margaret River Readers & Writers Festival. Mabel hopes to one day become a publisher and provide opportunities for other First Nations writers. CryBaby (Night Parrot Press) is Mabel's debut collection of micro memoir that follows her through all the seasons of life, from the brightest summers to the coldest, darkest winters and all the transitions and rebirths inBetween.

Questions & Curiosities

Welcome to Ruminations Mabel! It’s a pleasure to have you here. Can you begin by telling us a bit about yourself?

MG: Thank you for having me! I am a 25-year-old Yamatji girl and writer. I grew up down south in Kinjarling, also known as Albany, before my family relocated to Jambinu (Geraldton) in my late teenage years. At 18, I moved to Boorloo to study psychology at the University of Western Australia, where I was introduced to writing, which seemed to change the entire direction of my life.

Congratulations on the release of your debut book! It was so nice to catch you briefly at the launch — I’ve since devoured CryBaby and have lovingly tucked it away on my nightstand. How does it feel to know your first book is out in the world, finding its way into readers’ lives?

MG: Having CryBaby out in the world is both daunting and heartening. When writing for CryBaby I tried my best to make an honest piece of work which meant forgetting that anyone would maybe one day read it. And now that it’s out in the world I’ve been trying to avoid reading it from other people’s points of view. At first, I’d pick it up and cringe at my own writing imagining different people I knew sitting and reading it with their unique perspectives—and of course, in my head, everyone hated it. I had dreams that people would read the book and then just say nothing at all—nothing positive and nothing negative—and to me, no reaction was the worst possible outcome. But since CryBaby has been out in the world for nearly two months, I've received so many messages of love. So many readers see themselves amongst the pages of CryBaby and although that sometimes makes me sad, it’s quite beautiful that I’ve spent half my life feeling alone with my emotions unaware that so many people have felt the same.

It really is a heartfelt book. When I first realised it was a collection of micro memoirs I was intrigued — I think CryBaby is now the first and only one I’ve read. What is it that drew you to micro memoir as a form?

MG: I love short for writing, I think it’s a great place to start as a writer, although often I think it’s discredited by being labelled “easy” when saying something meaningful in such little words can be very clever. As soon as I discovered writing I found that micro memoir was where my voice could flow the most naturally and really, CryBaby is like a well-written diary. I find that I narrate my whole life in my head anyway so I may as well write it down.

“…editing to me is not the adding of punctuation or the correction of spelling but it is the dressing up of the piece of writing. And so every word must fight to be kept in the piece, every sentence must prove it belongs.”

I fell in love with how you were able to craft such rich, tangible vignettes with such brevity. I wondered if the writing process felt equally as brief, or if each word was a labour of love.

MG: I find that I separate the Mabel who writes and the Mabel who edits, so the writing usually begins with a stream-of-consciousness type of process where I try to get pure memory from thought on the page. That moment is often brief. But then I’ll edit and editing to me is not the adding of punctuation or the correction of spelling but it is the dressing up of the piece of writing. And so every word must fight to be kept in the piece, every sentence must prove it belongs. This is also where I might add things that connect my whole story in a bigger way. When writing CryBaby I wanted each piece to work on its own but I also wanted it to feel like a thread of string had weaved its way through the entire collection, tying the whole thing together, and doing this was definitely a longer more intentional process.

In CryBaby’s introduction, you mention initially feeling like your work was unpublishable, particularly in the context of an apparent desire for First Nations writing that centres “cultural politics or identity or trauma”. What advice would you give to other First Nations writers hoping to have their work traditionally published in Australia and who feel their writing falls outside industry expectations?

MG: My hope is that First Nations writers in the 21st century are able to write about any themes, genres, or topics they would like and that the industry can still recognise that as First Nations writing. I think that the publishing industry having expectations of what First Nations writing should be is just another way for colonisers to try and control the narrative of being First Nations in Australia. I don't necessarily have advice, but I would encourage First Nations creatives to challenge non-indigenous points of view of what it means to identify as a First Nations person in the 21st century.

Would you be so kind as to show us your altars, Mabel?

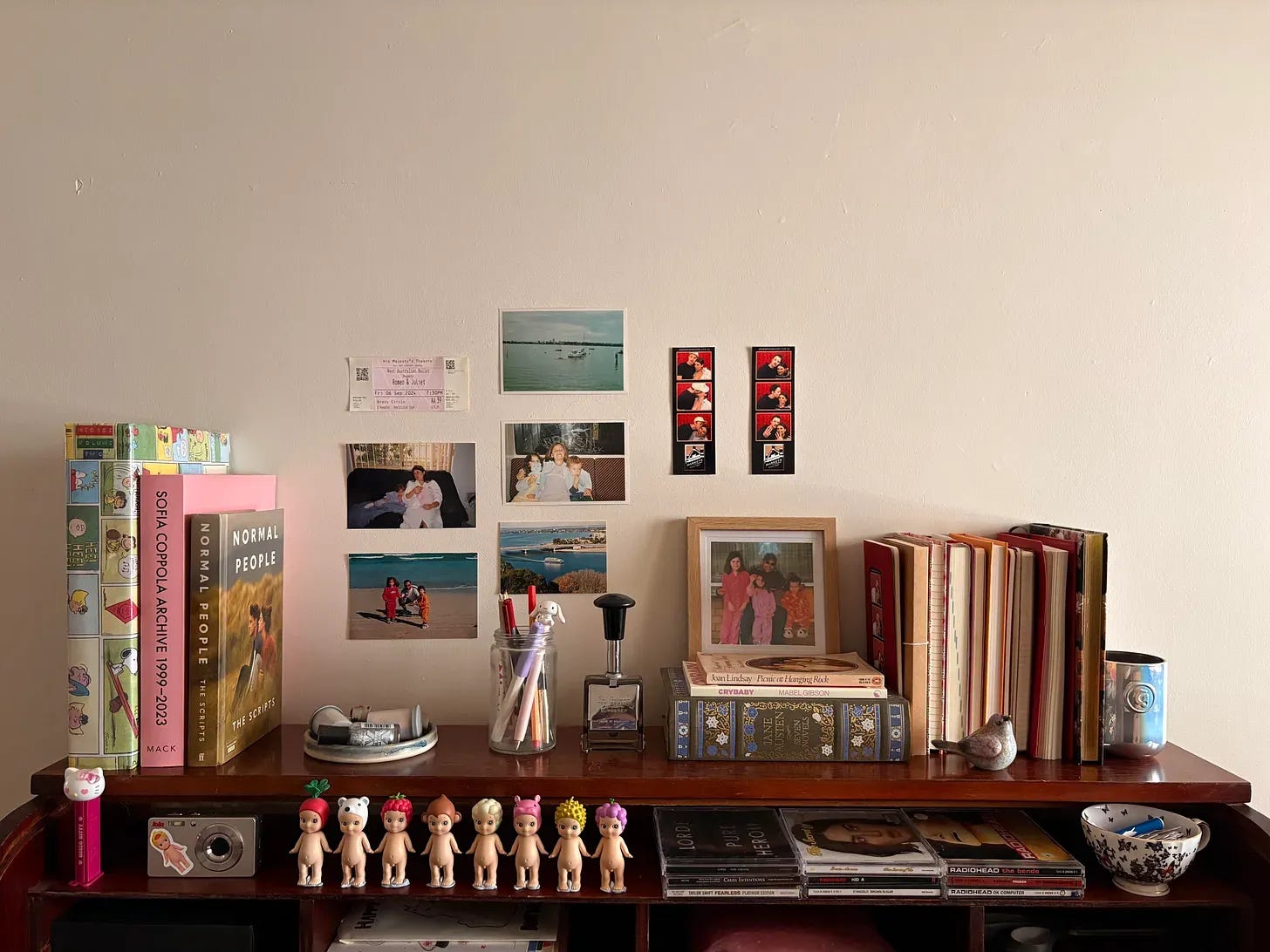

MG: I got my beautiful desk off Facebook marketplace for sixty dollars from a lady who was moving in with her son because her husband had just passed away. I like to think it was well-loved in its past lives just as much as it is loved in this one.

I am a collector of things, so even though you are seeing my desk in its very neatest form it never takes long to become cluttered again.

Although I love my desk, I don't always use it when writing. When I was 19 I was diagnosed with Graves disease and shortly after I went into a thyroid storm which resulted in the removal of my thyroid gland, so I spend almost 50% of my time in bed, including writing time. Over the years I’ve found working from bed to be easiest some days, which is of course a privilege but also sometimes my only option.

CryBaby’s nostalgic tone lends the collection a dreamy, fluid quality despite it being an accumulation of quite isolated, fragmented moments. One thing that consistently grounds these moments, though, is their connection to land and place. How does your connection to land shape your writing and in turn, your writing practice?

MG: I think since I was a kid I’ve always been extremely aware of the land I was on and its meaning and connection to me and I think that often comes across on the page without me being intentional about it. If you pay certain attention to things, they are bound to show themselves in some way through your writing—I couldn't write about myself without writing about the places that I’m extremely connected to and affected by. Place, land, and Country are all huge parts of my story and my emotions have often mirrored the environment I’m surrounded by. I see that so much of myself is made up of the places I have inhabited—I am a beach in Albany, a tree in Geraldton, a house on the corner of a street etc.

A note for free subscribers

To continue reading Mabel’s interview and unlock her creative prompt, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Doing so gives me the time to find and interview other inspiring guests for Altars & Artists. Your contribution also keeps Ruminations running & this lil writer at her desk! <3

Can’t afford a paid subscription? You can now earn complimentary subscriptions by sharing posts—you’ll be credited for any new subscribers to Ruminations!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ruminations to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.